- Home

- Sonya Hartnett

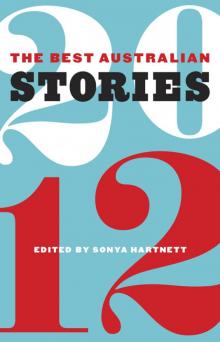

The Best Australian Stories 2012

The Best Australian Stories 2012 Read online

Copyright

Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Media Pty Ltd

37–39 Langridge Street

Collingwood Vic 3066 Australia

email: [email protected]

http://www.blackincbooks.com

Introduction & this collection copyright © Sonya Hartnett & Black Inc., 2012. Individual stories © retained by the authors.

Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of material in this book. However, where an omission has occurred, the publisher will gladly include acknowledgement in any future edition.

ISBN for eBook edition: 9781921870811

ISBN for print edition: 9781863955805

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

Contents

Introduction

*

Martin Lindsay

Someone Called Rob

Eva Lomski

And Senseless Acts

Sarah Holland-Batt

So Far North

Alex Miller

Ringroad

Emma Schwarcz

Sidney

David Astle

Oxtales

Bram Presser

Crumbs

Rebecca Harrison

Scissors

Chris Womersley

A Lovely and Terrible Thing

Erin Gough

Benny Wins Powerball

Romy Ash

Underwater

Marion Halligan

A Willowy Woman

Matt Gabriel

Other People

Ashley Hay

The Crow

Michel Dignand

She Knows How to Look After Herself

Liam Davison

The Other Room

Kevin Brophy

Aftermath

Greg Bogaerts

Market Porter

Sean Rabin

I Can Hear the Ice Singing

Kate Simonian

Scott

A.S. Patric

Guns ’N Coffee

Zoe Norton Lodge

Yia Yia on Papou

Jon Bauer

Cold Patch

David Sornig

Your Voice Is Lead

Eric Yoshiaki Dando

Human Beans

Meredi Ortega

David Davis at Coldpigeon Dot Com

Alan Gould

The Raid on Australian Poetry

Anthony Lynch

The Loveliest Night of the Year

David Brooks

The Swan

David Francis

Parts Unknown

James Bradley

The Inconvenient Dead

Brooke Dunnell

The First Day of the Season

Publication Details

Notes on Contributors

Introduction

Sonya Hartnett

On summer days when my brothers and sisters and I were young we sometimes used to visit our cousins, who had a swimming pool. Our cousins’ house was plush and tidy, very unlike our own home. The swimming pool was not the only attraction: my aunt was a librarian, and her house – also unlike our own – was filled with books. I would often pass our visits there reading on one of my cousins’ beds, or exploring the urban pine forest which reared, dusky and spooky, beyond the back fence. But this particular day was a hot day, and we were in the pool, my brother and younger sister and two of our cousins. We all must have been around ten or twelve years old. The swimming pool wasn’t large, but it was lovely. Our uncle had built a deck around it, and you could hang on the pool’s edge and rest your arms on the warm timber and let your feet drift unmoored. Glancing up, you would see the pine forest, a shadowy field of towering trees which shifted watchfully with the wind. Beyond their piked tips would arc the hot blue sky, and in the lulls of our laughter and splashing there was silence: I don’t remember any noise in the places of my childhood.

My sister Lucy, also a reader and usually a swimmer, wasn’t in the pool that day. She came out of the house carrying one of our aunt’s paperbacks, knelt by the edge of the pool and called us over. She was going to read us a story, she said, a short one. Occasionally at home she would do this – she’d read the entirety of The Chrysalids to me, so I knew her taste was trustworthy – but I doubted my cousins and brother, being boys, would have the patience for such an interlude. Lucy, however, was the eldest of us, and thus could sometimes force submission, and did so now. We trod water, the beach ball bobbed away, silence fell, we glided nearer; Lucy opened the book. I could see its cover was a strange one, ugly and stylised. ‘It’s written by a man called Roald Dahl,’ she told us; the name meant nothing to me. ‘The story is called “The Man from the South.”’

Thirty years later, yet I remember the day so well – not the whole day, perhaps, but the hour. Maybe my whole life found its shape as I hung listening on the edge of a swimming pool, the cool water choppy around me, the sky whitely arid above. While my sister read the story of a dapper little man who makes a startling bet with a young sailor, the stake being the little man’s car against the smallest finger on the young man’s left hand, I felt the heat of the deck rising through my palms, smelt the forest and heard it move. The bet involves the young man’s cigarette lighter: if he can make its flame catch ten times in a row, the dapper man will give him his green Cadillac; but if the lighter fails, the dapper man will chop off the sailor’s finger with a meat cleaver. The young man’s hand is tied to a tabletop to prevent him reneging on the deal, in an expert fashion that makes the narrator wonder if the gambler hasn’t done this before. The dapper man speaks with an accent – the writer, whose own name was peculiar, had written his words in a peculiar way – but my sister was good with voices. ‘Now pleess,’ she read, ‘clench de fist, all except for de little finger. You must leave de little finger sticking out, lying on de table.’

The forest, the sun, the water, the words: we hung suspended, we all did, our chins on the scorching metal of the pool’s rim, the beach ball bumping lightly, ignored, the boisterous boys quietened, listening to the sound of the cigarette lighter flicking and catching once – twice – three times, four times. It reached seven, and our fingers were digging into the deck, the forest itself was bending closer to hear. It was such a hot day, an airless afternoon, and the butcher’s cleaver which hovered above the sailor’s finger hovered over us too; we could draw breath no deeper than could the narrator, the sailor, the blonde girl in the bathing costume who’d been invited along as a witness to the folly – she wore bathers because it was a hot day in the story too, there was a swimming pool in the story, and a forgotten beach ball.

The sailor flicked his lighter, and my sister and the narrator cried, ‘Eight!’

*

I thought often about that long-gone afternoon in my cousins’ swimming pool as I read through almost 800 submissions for the 2012 edition of The Best Australian Stories. Eight hundred stories is a lot to read, and it took a long time, and often the sheer size of the project might have swamped me with indecision had it not been for the memory of that day, and the anchoring lesson which Dahl, that dazzling d

evil, that dark trickster of a short-story writer, taught: short stories are stories. Intrinsically and essentially they should be about plot. Among the submissions there were so many beautiful and skilful pieces of writing that they alone could have filled several anthologies: but in the face of so much choice – so much work of such quality that the whole experience has been an exercise in humility, for I’ve spent my life trying to become a decent writer and now I know for sure there are hundreds as good, and far better – it became vital to refine the conditions of acceptance. There are a couple of exceptions, pieces of writing which pleased me so much they just had to be included, but in assembling the collection I have generally adhered to Dahl’s great law: that the purpose of a short story is to tell a story. Nothing – not the author’s standing or lack of one, not the subject matter or style – has been more important than the degree to which the story keeps and holds the reader’s interest. Yet even under the guiding light of the master storyteller’s rule, finalising the selection has been one of the most anguishing things I’ve ever done. The anthology could have been three times longer than it is, and still I would have been forced to omit pieces I’d have liked to include. I will never look at the anthology without thinking of those left behind.

Nonetheless I’m proud of this year’s selection: one can never please everyone with such a collection, but I quite vainly hope Roald Dahl would like it too. I hope he would enjoy the black humour which runs through many of them, and the calm cool voice of others, and the craftsmanship which characterises them all. The stories come from all over Australia, as well as from Australian writers in far-away places around the world, but they share a delicate complexity and a vibrant cleverness. Decades ago, I held my breath as my sister cried ‘Eight!’: these stories, too, are breath-takers, the ones which render no thing more important than discovering what happens next. They are thirty-two fine examples of what well-placed words should do in tight confines.

Sonya Hartnett

Someone Called Rob

Martin Lindsay

It was an unknown number. I usually let them through to voicemail.

‘Is that Rob?’ A male voice, holding a temper ready to explode.

My ‘who wants to know?’ came across a little more abrupt than intended.

‘The boyfriend of Kate.’

The call now involved three strangers. I asked who Kate was to narrow things down.

‘Kate is the girl whose birthday card you signed at the pub the other night.’

Oh. Vague recollection. But wasn’t that my mate’s card? I asked the angry voice if he was sure.

‘You left this phone number.’

Oh.

More recollections. Later in the night. In the swing of beers. When many ideas suddenly seem unbackable winners. There was a chance Kate had been gorgeous, though equal chance beers were talking. At the time, she’d been gorgeous enough for me to cheekily gate-crash her birthday gathering next to ours. Then sign her card with a flirtatious witticism and … oh God … my mobile number.

The witticism. Less a sonnet, more a mildly pornographic pick-up line.

‘What are you playing at, making a pass at my girlfriend?’

Ah. That would explain the anger thing. I babbled an apology. Me drunk, hour late, beers many, and most definitely unaware he was on the scene in a romantic sense or otherwise.

‘Well,’ he said, fury barely subsiding, ‘just see it doesn’t happen again.’

I hardly remembered it had in the first place.

He hung up with a parting cuss, and I vowed hereto never to be talked into shooters when birthday cards were around.

It was twenty minutes later when the second call arrived. Another unknown number. ‘Is that someone called Rob?’ a female voice asked. I confirmed with less courage this time. ‘This is Kate. You wrote in my card.’

I explained that her boyfriend had just pointed out the error of my ‘harmless’ prank.

‘What did he say?’ she interrupted. ‘He didn’t threaten you, did he?’

‘Threaten’ had an insidious tone. I asked in what way.

‘Violently. Physically. Christ, you didn’t tell him your address, did you?’

I answered no, my mind on speed replay of the conversation. Had I given anything identifying? I hadn’t even confirmed my name. Safe. Reasonably. I assured her no threats were made besides some perfectly understandable anger in the circumstances.

‘You don’t know Adam,’ she warned.

This was true. I didn’t. Or her for that matter.

She thanked me for being so understanding, and I apologised again for the birthday card and trouble caused. Though I couldn’t help flirtatiously adding that if she didn’t have a boyfriend, the call might’ve turned out much better. She laughed politely, with the distant patronising tone that the contentedly coupled give lame approaches.

The phone rang again minutes later.

‘I cannot believe you,’ snarled the angry voice.

‘Adam?’

‘Barely half an hour after I tell you off for cracking onto Kate, you’re giving her secret calls behind my back.’

‘It wasn’t a secret call.’

‘It was secret from me.’

‘That’s as may be, but I wasn’t calling secretly. In fact, I didn’t call at all.’

‘What are you saying about Kate, then?’

‘Nothing. She didn’t say the call was secret.’

‘What did you think, her calling you?’

‘Not much. I don’t normally deduce the secrecy potential of calls from strange numbers.’

‘Mr Fancy clever talker, eh?’

‘A clever guy would’ve hung up by now.’

‘You do and I’ll crush you, mate.’

Fortunately, diplomacy genes run in my family. I invoked the universal signal of utmost seriousness between guys. ‘Dude,’ I said carefully, ‘I don’t have designs on your girlfriend. You’re a lucky man and I wish you all the best with her. Nothing is going on.’

A wavering silence. The ‘Dude’ had done its work. Then, ‘There better not be. Because if I find out you’re calling each other again …’

‘I don’t even know her number,’ I fibbed. I would be clearing my phone history as soon as the call was over. ‘It’s as good as forgotten.’

His silence suggested uneasy contentment. I bade him goodwill on his way. There was a conversation about to be had between them, and I was glad to be no longer involved in it.

*

According to call history, she rang three more times.

I put the relevant numbers on block, deactivated my voicemail, then steadfastly refused to answer unknown callers for the rest of the week.

A completely different number called on Sunday afternoon. An ill-thought-out sense of security led me to answer.

‘Who the frick do you think you are?’ a venomous female voice asked.

‘I don’t know. Who do you think I am?’

‘Some thoughtless bastard stirring up trouble in someone’s relationship for a laugh. Surely you know how rocky things are between Adam and Kate?’

I groaned at the names, then asked hers.

‘I’m Kate’s best friend. I look out for her when pricks like you come along to screw things up for her.’ My protest was ignored. ‘Adam’s furious. He’s talking about ending it all.’

‘What, suicide?’

‘With her. He doesn’t trust her anymore. What with you leaving messages and suggesting things.’

‘I don’t even know her. If anything, she’s been ringing me.’

‘Don’t try blaming this on her, you bastard.’

‘I’m not.’

‘Just as well, arsehole. Things are still tense between them about the whole Scott thing.’

<

br /> ‘Who’s Scott?’

‘Don’t try acting stupid.’

‘I’m not acting.’

‘Scott was the guy Adam thought Kate was seeing behind his back. And we all know what happened between Adam and Scott.’

‘No, we don’t.’

‘Well, you wouldn’t want it to happen to you.’

This is exactly what you don’t want to hear in the information age. In fact, the information was ageing me at a fast rate. I had visions of this Adam guy googling me down. A mobile number and first name were probably enough to clean out my bank account, let alone trace my address. He might sneak round while I was in the shower and strangle me with the last of the toilet paper.

For all I knew, there was a picture online of my house, with me looking out the window wondering who was driving the strange van going by with a camera.

‘Why does Adam keep jumping to these sorts of conclusions?’ I asked. There was a scoffing sound at the other end. She was either disgusted by the question or clearing her throat. ‘Why did he think Scott and Kate were seeing each other?’

‘Because they were. God, everyone knew that.’

‘Except Adam, presumably. To begin with, anyway.’

‘This isn’t a laughing matter. Adam’s severely pissed.’

I glanced at my door to ensure it was locked. ‘My intentions in all this were entirely honourable.’ I gave my inebriated self the benefit of the doubt. ‘I didn’t even have any intentions. It was just a drunken joke.’

‘Oh, charming.’

‘I thought Kate was single,’ I said, slowly and deliberately. ‘I discovered she isn’t, so I’ve backed well away. Over the hill and miles away. I explained that to Adam. I thought, anyway. So hopefully this is the last he, she, you and especially me hear any more of this.’

Butterfly

Butterfly The Midnight Zoo

The Midnight Zoo Stripes of the Sidestep Wolf

Stripes of the Sidestep Wolf The Best Australian Stories 2012

The Best Australian Stories 2012 Golden Boys

Golden Boys The Children of the King

The Children of the King The Ghost's Child

The Ghost's Child What the Birds See

What the Birds See Thursday's Child

Thursday's Child